Photo: Clemens Habicht

‘L’ACTE GRATUIT’

GALERIE ALLEN, PARIS

Dec 4, 2014 - Jan 17, 2015

GALERIE ALLEN, PARIS

Dec 4, 2014 - Jan 17, 2015

If the world were clear, art would not exist.1

Mel O’Callaghan focuses on the experience of the self through the work's process.2

Describing art as a panacea for life, Nietzsche disclosed that “art is not an imitation of nature but its metaphysical supplement.”3 Albert Camus's philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus4 employs tragedy as a metaphorical device by which one may interpret the nature of self. Sisyphus was condemned by the gods to ceaselessly roll a rock to the top of a mountain only to watch it fall back down under its own weight. Camus reasoned that Sisyphus was conscious of his plight, and that through endurance he succeeds in accepting the absurd position he finds himself in, concluding, "I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain!”5. Camus likens our being to the factory employee, “every day in his life at the same tasks, and this fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious."6 Unconsciousness has been the goal of life’s dance for many varied civilisations and it is the aim that this liminal state may bring ascension. Camus concludes that the “uncertainty (of life) could be resolved through art.”7 With this exertive state of attainment we may sublimate our concept of labour with ecstasy.

For O’Callaghan, myth is a symptom, ritual a gesture of that symptom, and through artistic creation the artist may confront and resolve that symptom. The capability of both art and ritual to resolve one’s existential paradox and reassert human dignity is where artistic creation attains its highest value. The Greek word for rite is dromenon8, ‘a thing done’, which implies that to perform a rite you must do something. When re-enacted it becomes a ritual. Reminiscent of the repetitive nature of art practice, man tends to re-enact what he feels most strongly.

For her exhibition at Galerie Allen titled, L’acte gratuit9, Mel O’Callaghan focuses our attention towards the act of making (doing) itself. Each work is evidence of this act, the result of that act, and a mediation on the will that compels one to make (do). Installed in the gallery is a large-scale regent structure of connected espaliers10, Framework, 2014. Closed on all sides excluding several entry and exit points, the structure looks like a lattice chamber. It’s dormancy however is only short-lived as we, the audience, activate it by passing through. A transcendent bridge between ritual and art. To exist in this space a certain physiological precondition is indispensable: intoxication.11 The resistance and repetitive activity needed to strengthen our bodies echoes the routines of our daily lives. Through both these activities we hope to transcend our previous level. This expanse of vertical columns and horizontal bars conjures images and memories of redundant northern European gym apparati. Each espalier taken alone implies action, almost calls for it, the structure, defines it, a sportif Dan Graham pavilion that exposes the processes of perception and certain expectations in a quasi-functional space. Strengthening the artist’s concept of ritual process, the wooden sequence doubles as a type of passage. As one passes through the threshold they become a performer and part of a larger work. One part of a communal experience.

These stage-like structures oft build the framework, literally, for O’Callaghan’s performance pieces. In 2014 she presented Parade at the Biennale of Sydney and Time To Act as a solo exhibition at the Museum Medeiros e Almeida, Lison. Each required a large number of untrained performers to re-engage with the work multiple times. Parade was performed by 70 performers, 300 times, over a 3 month period. Ritual-like, these performances require a collective action undertaken in a delineated liminal space12, where the performer exists in a type of limbo. Unable to return unchanged, they exit transformed. Like one who entered a greek theatre and finds himself on sacred ground, the artistic performer’s entrance into the arena is an act of worship. Alexi Glass Kantor described this element of O’Callaghan’s practice as a type of, “jouissance, converging spectacle, performance and image into a synthesis where process becomes exponential and it is impossible to anticipate anything other than the end, so the players move fatefully and fitfully through endless conundrums of order and chaos…Within the gesture, the convulsing repetitions, there are infinite differences, which are imperceptible. And it’s this play of nuances leading to a silent insurrection through which we understand something fundamental is at stake”.13

Accompanying the structure of espaliers are a series of objects imbued with potential for activation, Impression and Foundation, 2014. Each straddles both working (process) and resolution. When emotion quietens, the form produced does not become an end in itself. For the artist who makes, only to make again, the physical deposits of such action are fragments in a much larger process. With Impression, 2014, the artist mounts what appear to be canvas crash matts to the gallery wall, forming a tableau in hues of utilitarian tones. Padding, rivets and ropes work like geometric abstractions, compositions that run with function. Each matt conjures physical trauma and the psychological state of one who may predict or prevent the action of crashing.

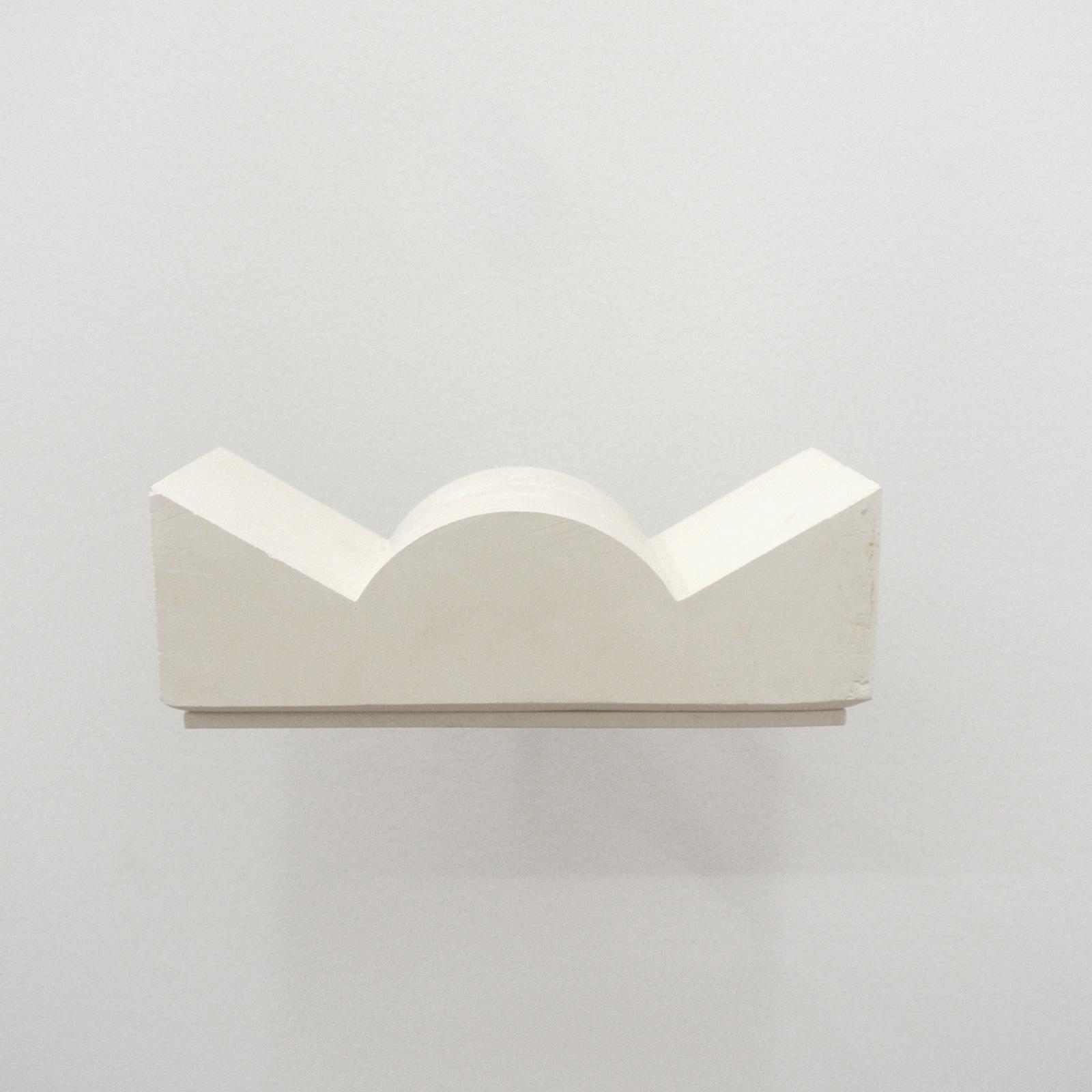

Protruding from a wall on individual mantels are twenty delicate ceramic forms, Foundation, 2014. Acquired during research into casting, each is a tool once used as a weight or counterbalance in the creation of a work of a master ceramicist.14 Each object provided the structure and foundation, support and balance, that was required during the forming of the object he desired. The forms of Foundation are uncannily similar to the work the artist was casting herself. As the unused results of another’s process these chalky white casts are the by-product of the repetitive practice – a physical representation of the performative act. The sculptures achieve what in life we cannot - an end.

The violent and pointless actions in O’Callaghan’s works can be seen as destruction in order to create. The physical labor might not only be seen as repetitive and violent, but also as introspective and meditative. In this way, figures seem to be distancing themselves mentally from the act and the site of endurance.15

A new colour video work, L’acte gratuit, 2014, concludes the exhibition, giving a key to the other works. It hints at an action that is obviously gruelling and yet unseen. A male face, cropped-in tightly, appears and then exits a locked-off frame. Progressively we witness his mounting exhaustion as sweat appears upon his brow and his breath becomes shorter. A bell is heard off-screen and we discover that he is a boxer returning from his fight, reappearing in-frame even more depleted. Out of frame is the liminal space (the ring) where the protagonist undertakes his rite - an exhaustive dance that delivers him closer to pain and disintegration. We question his recurring return to the fray, his decision to undertake more physical pain, and wonder if he has received any illumination or are we witness only to his continual demise. Like Sisyphus, this man accepts the absurd order of things and re-enacts his struggle, giving precedence to process/praxis over achievement. Likewise the viewer also experiences this catharsis as he feels the boxers pain and imagines himself suffering. As in Framework, this process is experienced collectively. A socio-cultural catharsis of selves, not self.

Victor Turner in Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure16 notes that in ritual and performance the method of working is more valuable than a finished piece. O’Callaghan sees her work as fragments of process, each holding within a call for outright action. Art and ritual go hand in hand, they explain and illustrate one another.

1 Camus, Albert, Le Mythe de Sisyphe, trans. J O’Brien, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1975

2 Schneider, Anja Isabel, Catalogue Essay, Mel O’Callaghan, Each Atom Of That Stone…In Itself Forms A World, 2010.

3 Nietzsche, Friedrich, The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings, Ch. III trans. R. Speirs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999

4 Camus, Albert, Le Mythe de Sisyphe, trans. J O’Brien, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1975

5 ibid.

6 ibid

7 ibid

8 Harrison, Jane Ellen, Ancient Art and Ritual, Oxford University Press, 1913 p.13

9 The title of this exhibition refers to an act without immediate purpose. Andre Gide introduced the concept in a study of Dostoyevsky and developed the concept it further in his, Vatican Cellars.

10 Developed in Sweden in the 19th century by professor Pehr Henrik Ling the espalier is a climbing frame for building muscle and cardiovascular workout.

11 Nietzsche, Friedrich, The Will to Power, published by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, 1906

12 Turner defines the notion of liminality as the transitional state between two phases, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, Aldine Pub. Co., 1969

13 Glass Kantor, Alexie. Catalogue Essay, Mel O’Callaghan, Each Atom Of That Stone…In Itself Forms A World, 2010.

14 Guy Eliche, Paris, France

15 Schneider, Anja Isabel, Catalogue Essay, Mel O’Callaghan, Each Atom Of That Stone…In Itself Forms A World, 2010.

16 Turner, Victor, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, Aldine Pub. Co., 1969

17 Camus, Albert, Le Mythe de Sisyphe, trans. J O’Brien, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1975